What is diversity? Why must we, as geographers, be concerned with how our work addresses power disparities and social differences?

Stevie Larson, PhD, studies race and decolonization, histories of organizing, and governance in relation to transnational Asian adoptees and Asian America more generally. In the profile below, as in his research, Stevie engages with the difficult questions that underlie conversations on diversity: why are people valued differently, and how do their struggles impact our social conditions?

We are excited to share that Stevie Larson has accepted a position as Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College in Atlanta, to begin in Fall 2016. For more information about Stevie’s research interests, teaching experience and visualizations, including posters and maps, please visit : http://geostevie.web.unc.edu/

This is the second in a series of features to be presented by the Diversity Committee of the Department of Geography. Through these profiles, we seek to highlight the broad array of research, teaching and advocacy work our undergraduates, graduates and faculty undertake to address questions of power and injustice.

Posing with the cast of I Was Never Alone, a research play by Cassandra Hartblay on people with disabilities in contemporary Russia, 2016

Diversity Research Profile: Stevie Larson, PhD

- How do you define “diversity”?

Diversity is a window into the ongoing differentiation of human society. What I mean by this is that the most familiar forms of human difference – race, gender, sexuality, class, nation, religion, culture, disability, age etc. – tend to be legible to us through distinct identities that are historically and geographically produced. ‘Diversity’ is the name I give to the political commitment toward recognizing these multiple identities as more than just variations from a norm or ‘token’ representative voices from marginalized groups, but rather as entirely different ways of living and experiencing the world that are valid on their own terms. This is just a window, though! The actual world is far messier and grander than these identities allow us to see.

- How have diversity questions or issues shaped you as a scholar?

I was never all that concerned about diversity questions or issues when I was an undergraduate. At the time I was an activist who liked to talk a good talk about feminism and racism and globalization’s war on the poor, but I hadn’t put in the effort to develop an analysis around any of it. After I graduated I happened to end up living and working in New Orleans in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which substantially evolved my work as an organizer. I was prodded to seek out intellectual spaces for all of my restless thoughts about race and class in a majority Black city that was criminally abandoned and positioned in the worst conditions of ‘premature death’, as Ruthie Gilmore puts it. Additionally, I’ve had the honor of participating in a social movement research group, Team Colors Collective, which takes a refreshingly broad view of working-class struggles in the US that includes women’s informal labor (i.e. domestic work, sex work), poor people’s movements, and the Black Radical tradition. The work I’ve done with them helped set the foundation for my scholarly research and its orientation to the nuanced dynamics of race, class, and gender (among others) in the US.

Stevie participating in the APIA Spoken Word & Poetry Summit, 2011

- What challenges or possibilities do you see for the discipline of geography as related to diversity? What can we do to address these issues in geography?

Academia is like any other industry – it’s never a great place to be when you’re on the margins, and yet, those marginalized folks can do incredible things with the spaces and resources they have at their disposal. Geography in particular has seen enormous strides in feminist approaches and scholarship, as well as some newer efforts to develop geographies of race (and Black geographies in particular). Without both of these traditions – and a lot of hard work by faculty and students to collectively produce them and keep them going! – my own work would suffer, as would the discipline. But feminist and critical race geographies still face a long uphill climb to be recognized as valid, interesting, and indeed, game-changing work (which they are). My usual prescription is more and better organizing: collectives of scholars at and across institutions; dialogues at conferences that are focused on specific diversity issues; and any and all ways to get and keep warm bodies in all the rooms, including targeted recruitment of nonnormative faculty and students, scholarships and grants for diversity-based research, and robust mentorship structures for folks who enhance the diversity of their programs (either by their identities, experiences, or the work they do). None of this is impossible, but it requires political will and commitment.

- What is your research focus and how does it relate to diversity? Why are diversity issues important in your research?

My research focuses on the political impact of ‘new’ Asians that migrated to the US during and after the height of the Asian American movement of the 1960s, a sprawling group that includes transnational adoptees (especially from South Korea, Vietnam, and China), refugees from Southeast Asia at the end of the Second Indochina War, ‘preferred labor’ markets of middle and upper-class folks from East and South Asia (now often referred to as the ‘model minority’) and undocumented women laborers in the domestic work industry, among others. This unruly diversity among Asian Americans is incredibly important to me (and should be important to everyone else); it not only explodes the common framing of Asians in the US as a monolithic group, but also, its primary consequence – the implosion of the ‘pan-Asian’ unity that the Asian American movement had promoted – is not unique at all: similar rifts developed at the same time, especially between the Black middle class and Black poor folks, mainstream gay/lesbian politics and more marginalized queer/trans struggles, and a professionalized organizer class (including many nonprofit workers) separated from mass grassroots movements. We do ourselves a great disservice by ignoring these divides in our current political moment. However, this internal differentiation and diversity within communities is not always a problem; it often paves the way for new understandings and new relationships that otherwise are precluded when people lock into a show of group unity.

- Who inspires you in diversity-related work, whether that is a scholar you follow, an activist, or another role model?

I have far too many sources of inspiration! Recently, however, I have had the pleasure of working with two collective efforts that exemplify a real intentionality towards honoring the ‘messiness’ of diversity I’ve been talking about. One was the national Asian/Pacific Islander American Spoken Word & Poetry Summit, which was held in my home state of Minnesota in 2011. For two years I worked with an organizing crew of twenty people to orchestrate this summit, and from the crew’s make-up to the programming we arranged, we embodied and pursued practices that opened up spaces for marginalized groups to freely claim and use as they needed; during the Summit, for example, we had adoptee, mixed-race, and Desi (South Asian) caucuses, as well as prayer and meal accommodations for those in our community honoring Ramadan. This summit was also my first introduction to radical adoptee politics, which became the focus of my dissertation. I’ve also worked throughout my graduate career on disability issues, especially thanks to the leadership of Cassandra Hartblay, a recent Ph.D. in Anthropology. She and I co-founded the Carolina Coalition for Disability Justice, which built a network of faculty, staff, students, and community members interested in the experiences of people with disabilities. We arranged multiple events and programs highlighting disability justice issues on campus. Like Asian America, disability is also a very loose term that fails to capture its internal diversity and divides; participating in this organizing with Cassandra continues to remind me just how ‘normal’ nonnormativity is, an idea that underscores my dissertation and overall research program.

- What are some of the implications related to diversity from your writings/publications?

One of the aspects of diversity I’ve really enjoyed exploring in my writings is how ongoing human differentiation compels everyone into all kinds of actions and strategies for negotiating, resisting, and surviving domination based on these differences (i.e. patriarchy, racism, ableism). And I mean everyone – not just the marginalized ‘others’! I’ve always been bothered by common perceptions that diversity is only a significant factor for folks on the losing end of human difference – the ‘wrong’ gender, the ‘wrong’ race – when in reality, patriarchy has unquestionably limited and deformed the possibilities for men’s lives, and racism has stunted white folks everywhere. Frantz Fanon, June Jordan, and James Baldwin all gave us the framework for this notion; our task is to give it additional scholarly heft. I’m writing an article right now for Environment and Planning D (a special issue co-organized by Sara Smith and Pavithra Vasudevan on race, biopolitics, and futurity) that explores one aspect of this further, namely, the impossible demand placed on whiteness for security and permanency, and what happens when this is further unsettled in conditions of generalized debilitation due to economic restructuring and political demobilization in the US. We need more of this kind of scholarship to complement contemporary diversity research and challenge its practitioners to look beyond their typical focus on marginalized groups.

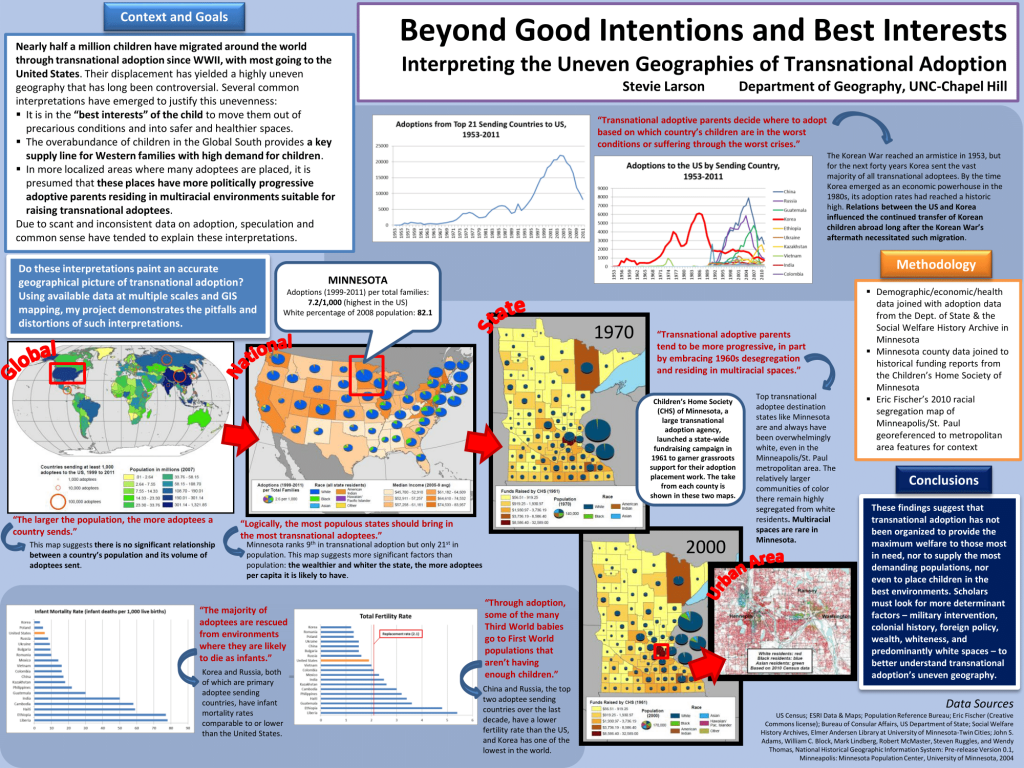

Poster by Stevie debunking common myths about the uneven geographies of transnational adoption

In the news:

Stevie profiled in the Daily Tar Heel for his work with Asian American students at UNC, particularly the RadAsians (Link: www.dailytarheel.com/article/2015/03/students-explore-asian-american-identities)

Stevie recognized by the Department of Geography for his dedication to teaching (Link: https://geography.unc.edu/2015/04/16/phd-student-stevie-larson-has-been-awarded-the-cecile-daniel-osment-graduate-award/)

Publications:

Larson, S. (2013) Making Exceptions: Rethinking Success through the Lives of the Siamese Twins. Amerasia Journal, 39:1, 60-74.